Ecocide is Legal

Tar Sands, Ecocide Law, and the Limits of Systemic Change

Welcome! I’m Max Wilbert, the co-author of Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It and co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass. This newsletter focuses on sustainability, greenwashing, and resistance. You can subscribe for free. Paying for a subscription supports my writing and organizing work, and gets you access to behind-the-scenes reports and unreleased drafts.

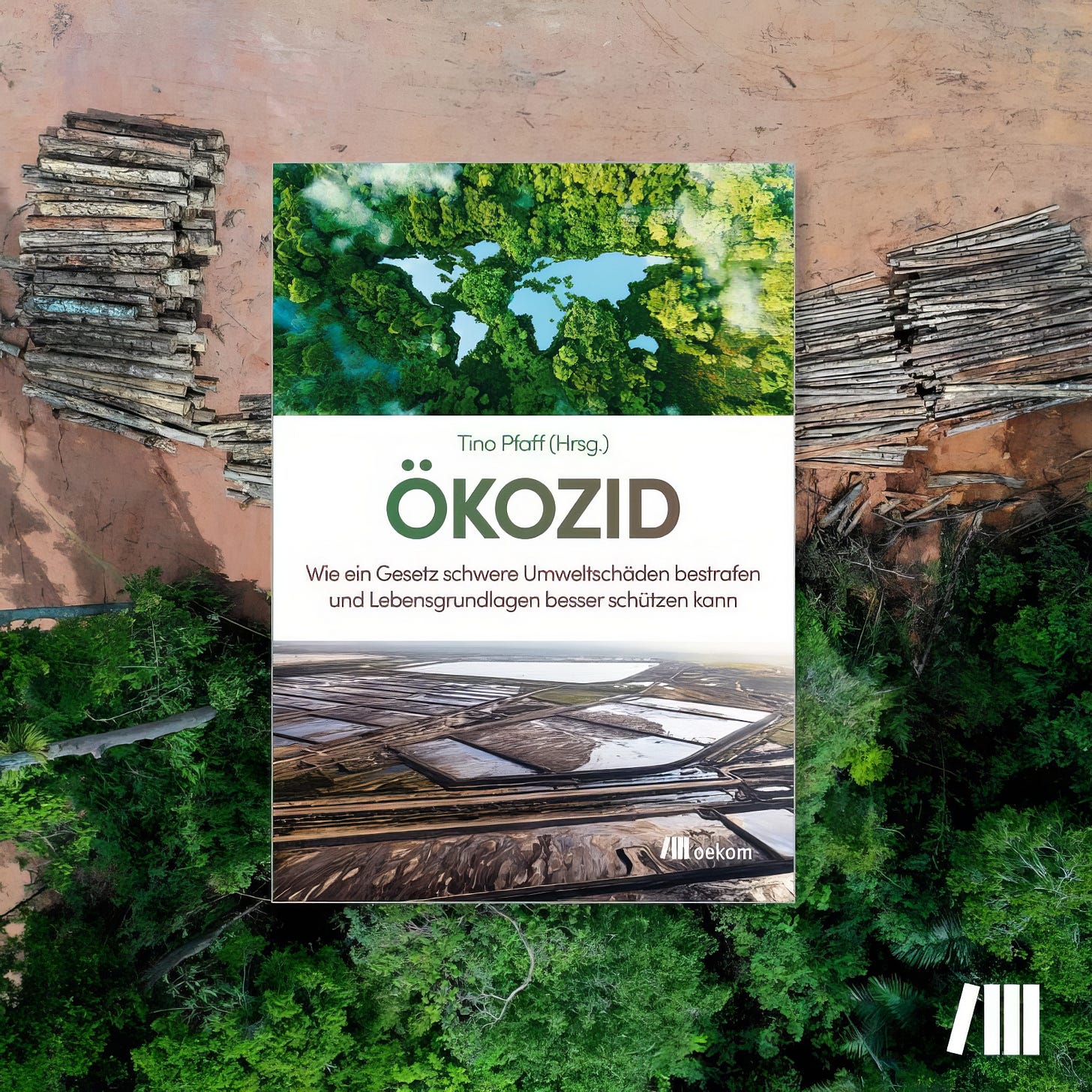

Last year, I was asked to write an essay focusing on Tar Sands for inclusion in a German-language book on ecocide law. This is what I wrote, which has never been published on the internet, or in English.

Abstract:

The struggle to halt the ecological crisis may be greatly assisted by ecocide law. Major environmental crimes are a crisis. But, most of the destruction of the planet is legal. This is true of the Alberta Tar Sands, the largest and most destructive industrial project on Earth. The legal system of most of the world’s nations is dominated by corporations and is deliberately set up to facilitate the exploitation of the natural world to generate profit, growth, and development. In this context, a new legal framework including strengthening criminal liability for perpetrators of ecocide is necessary, but not sufficient. The ecological crisis is multifaceted, global, and deeply embedded into the structure of economics, policy, and culture. Effectively halting and then reversing the ecological crisis will likely require dynamic grassroots movements employing a wide range of tactics and strategies including, but not limited to, legal strategies, education, non-violent direct action, legislative change, and even eco-sabotage and other “radical” actions.

Movements for justice have always used the legal system as an arena of political struggle. Feminist legal scholar Catherine MacKinnon, who is credited with the legal recognition of sexual harassment in the United States, said it concisely: “law organizes power.” [1]

There is no doubt that our planet is in crisis and in dire need of an effective environmental movement. Extraction of primary resources—timber, foodstuffs, ore, fossil fuels, water, etc.—has tripled over the past 40 years to more than 70 billion tonnes annually. [2] Greenhouse gas emissions have doubled since 1980, and more than 1 million species are threatened with extinction, threatening to unravel the ecological basis of life on this planet. [3]

This crisis has deep roots. The old-growth forests of Europe, Mesopotamia, North Africa, eastern North America, and east Asia were destroyed with hand axes and draft animals long before fossil fuels. [4] We can’t ignore the role that monocrop agriculture and the rise of urban civilizations has played in the unfolding ecocide.

However, over the last century, the widespread use of fossil fuels has facilitated explosive growth and unprecedented interconnections in global economic systems, and powered agricultural and medical advancements that have led to a human population of more than 8 billion. The most important fossil fuel is oil, which fuels global transportation and resource-extraction machines and is the feedstock for the majority of plastics and oil-based chemicals. This system is by definition unsustainable, since fossil fuels are finite and their use is undermining the ecological system.

Something has to change. But thus far, oil production continues to rise. As so-called “conventional” oil has peaked in availability, [5] demand pressure combined with new technology has meant that unconventional sources such as “fracking,” deep-sea drilling, and tar sands have become economically viable. In fact, they’ve become necessary to maintain economic growth in a capitalist system in which lack of growth rapidly becomes a systemic crisis (the fact that these energy sources have much lower energy return on energy invested, or EROEI, when compared to conventional oil is a topic best left for another article). Tar sands, fracking, and deepwater drilling have been lifelines for global capitalism and accelerants for ecological destruction.

Tar sands is a form of dense sludgy oil also known as asphalt, which has been used for paving roads for more than 120 years. But due to the difficulty in refining bitumen into oil, the business of refining tar sands into oil only began to explode as rising oil prices made this process profitable around 2001/2002. Today, the vast majority of the world’s tar sands oil is produced in Canada. Elsewhere around the world, tar sands oil is produced in Venezuala, Madagascar, Congo, and the United States.

Compared to conventional oil extraction—already a dirty and polluting process—tar sands extraction is even more harmful. It causes deforestation, pollutes water and air, harms and displaces wildlife, and is responsible for roughly 30% more carbon emissions than regular oil. Tar sands projects in Canada are also associated with drug use, sexual violence, crime, cancer, and other social problems in remote communities near the mines.[6]

[Since this article was written, researchers have found that the Alberta Tar Sands produce as much air pollution as all other sources in Canada combined.]

As a grassroots environmentalist, I’ve been involved in two community campaigns over the past 15 years opposing tar sands oil extraction and development which provide instructive lessons on ecocide.

Bellingham’s Tar Sands Pipeline

Bellingham is a city located just a few miles from the Canadian border in the northwestern part of the United States. The people of Bellingham know the dangers of pipelines. On June 10, 1999, a gasoline pipeline running underneath the city ruptured. An 18-year-old boy fishing in a creek was overcome by the vapors, fell unconscious, and drowned. The highly flammable vapor then ignited, causing a massive explosion. A pair of 10-year-old boys playing in the creek were severely burned, and both died. [7]

In 2010, an oil pipeline running beneath the city that carries crude oil from the Canadian tar sands to nearby refineries was up for renewal with the city. A group of community activists, including myself, decided to start fighting the tar sands pipeline. We began by holding public forums to educate local residents about the harms of the tar sands, pressuring public officials, and speaking with the media.

After months of effort, the city council started to agree with us—but the city attorney advised council members that if they failed to renew the pipeline lease, the pipeline company would sue the city, and the law would be on their side. “It comes down to the Commerce Clause,” the council told us, referencing a section in the U.S. Constitution that reserves to the Federal government the power to regulate interstate and international trade. Because the pipeline crossed an international border, the local government could not legally stop the pipeline from operating, even if every single citizen in Bellingham voted to do so.

In the end, the council passed two nonbinding resolutions. The first expressed Bellingham's opposition to the tar sands, and the second resolved to avoid tar sands fuels in the city vehicle fleet. [8] The local business journal described the resolutions as being intended to “gently steer” the city away from tar sands oil. [9]

Today, U.S. corporations have protection under the First, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution, as well as under the Contracts Clause. As corporate anthropologist Jane Anne Morris writes, “Corporate persons have constitutional rights to due process and equal protection that human persons, affected citizens, don’t have.” [10]

Thanks to education from corporate power activists, we knew this when we started organizing against the pipeline. But we did it anyway, because we wanted to test the democratic process and see if we could use the system to make change. We couldn’t, despite the fact that Bellingham had passed one of the most progressive municipal climate action plans in the nation, and the fact that the majority of the population and the city council were on our side.

I reached two conclusions from this experience. First: the legal system is dominated by corporate power. This is no surprise, as the United States was founded as a colonial enterprise (a business venture). Second: different tactics are needed. The classic social change methods of education, outreach, and government engagement are insufficient in the current situation.

The Utah Tar Sands

Several years later, I moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, and became aware of several proposed tar sands mining projects in the Tavaputs Plateau region. This rural area situated at 2,500 meters elevation is covered in dense juniper, scrub oak, and sagebrush which make up the best remaining habitat in the state for Rocky Mountain Elk, Mule Deer, Black Bear, and Cougar. Unmarked, often muddy dirt roads make travel dangerous, and deep valleys plunge thousands of feet to the rivers that drain the region – the White River to the north, and the Green to the west. Downstream, both flow into the Colorado River, which provides drinking water for 12 million people.

Thirteen thousand hectares of state lands situated on the southern rim of the basin—130 square kilometers—have been leased for Tar Sands extraction. If the mine were built, it could produce 50,000 barrels of oil per day. Dozens of similar mines are planned across the whole region. Along with their friends in state and local governments, energy corporations are collaborating to turn this region into an energy colony – a sacrifice zone. Twelve to 19 billion barrels of recoverable tar sands oil is estimated to be located under the rocky bluffs of northeastern Utah. It’s a drop in the bucket for global production, but it means total biotic cleansing for this land.

Resistance to tar sands and oil shale projects in Utah dates at least back to the 1980’s, when David Brower and other conservationists successfully fought off the first round of these energy projects. [11]

Forty years later, the fight is still on, so I started attending local meetings of several activist groups and visited the site of the PR Springs tar sands strip mine. The test pit looked like an open wound: a two-hectare hole gouged into the Earth, the bottom puddled with water and streaked with black tar. Churned earth and broken and tangled logs stretched on either side.

During the years I lived in Salt Lake City, our tactics included public education and outreach, pressure on government officials, investor relations, and non-violent civil disobedience such as disruption of industry meetings and blocking of access roads. Luckily, the economics of Utah tar sands has always been marginal, and to this point, the challenge of making a profit combined with determined community resistance has kept this region from full-scale destruction.

Tar Sands and Ecocide Law

Ecocide law could be an important new mechanism for addressing certain types of crimes against the planet. It is especially important to hold individuals responsible for the action of corporations (which are often limited in their liability) to create disincentives for bad behavior. Functional communities hold people accountable for their behavior.

Common sense says that tar sands corporations and the governments that enable them should be considered as among the most egregious violators of any ecocide laws. But, if ecocide is defined as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts,” [12] as proposed for the Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide in June 2021, then the tar sands projects discussed here—the Alberta Tar Sands, Utah tar sands, and Bellingham tar sands pipeline—could fail to meet the definition of ecocide.

There are two reasons for this. First, these projects are legal under existing law. Second, they may or may not be “wanton” (with reckless disregard for damage which would be clearly excessive in relation to the social and economic benefits anticipated); the interpretation of this is subjective and would depend on a court.

French Liberal School economist and laissez faire advocate Frederic Bastiat provided one of the most concise definitions of law within capitalism. “When plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men in a society,” he wrote in 1850, “over the course of time they create for themselves a legal system that authorizes it and a moral code that glorifies it.” [13] With his statement, Bastiat was attempting to critique socialism and collectivist tendencies. Marx, a contemporary of Bastiat, called him “The shallowest and therefore the most successful representative of the apologists of vulgar economics.” [14] But Bastiat has inadvertently provided a functional description of law within modern capitalism.

Given the current supremacy of the capitalist state, the courts are an important arena of political struggle. To put it simply, despite their ineffectiveness thus far as an arena if change, we are stuck with them. To concede this battleground would be a mistake.

But to rely only on legal methods is also a flawed strategy, as I have seen more recently with my involvement in the movement to protect Thacker Pass from lithium mining. [15] Despite highly irregular permitting under the Trump Administration, this highly biodiverse indigenous sacred site is currently being destroyed despite lawsuits from environmental groups, ranchers, and Native American tribes. My friend Will Falk, an attorney representing the tribes in Federal Court, often says that “the law will not save us.”

Legal reform has never proved itself able to do more than slow the progression of the ecological crisis. David Brower, the founder of Earth Island Institute and Friends of the Earth, and former director of the Sierra Club once said, “All I did was to slow the rate at which things are getting worse.” [16] In this historical moment, we don’t have time to merely slow the destruction. We need to rapidly halt it and to reverse it. This means choosing effective methods.

We can’t ignore the scope of the challenge. As Brad Hornick wrote in Resilience, “[Stopping the ecological crisis] implies a radical retrenchment or collapse of the dominant industries and infrastructure based upon fossil fuel production, including automobiles, aircraft, shipping, petrochemical, synthetic fabrics, construction, agribusiness, industrial agriculture, packaging, plastic production (disposables economy), and the war industries.” [17]

In other words, stopping the ecological crisis means transforming the global economy so fundamentally that we might as well call it a revolution. Stopping the destruction of the planet means ending the modern way of life as we know it. This reality is not popular in society, nor is it politically acceptable in courtrooms. But humans can adapt to ecological limits; the laws of physics and ecology will not shift to accommodate us. We must be adults and accept reality as it is, not as we wish it was.

The struggle to halt the ecological crisis may be greatly assisted by ecocide law, but we must never forget that most destruction of the planet is legal. For every Deepwater Horizon disaster there are millions of everyday disasters; as the satirical website The Onion wrote in the aftermath of that terrible oil spill, “Millions of Barrels of Oil Safely Reach Port in Major Environmental Catastrophe.” [18]

Business as usual is a crisis

It is self-evident that if our legal systems effectively protected the planet, we would not be in a crisis. Even victories, like the news as this goes to print that a group of children have succeeded in their lawsuit arguing that the government of the U.S. State of Montana has a fiduciary responsibility to consider climate impacts when permitting infrastructure and development projects, are partial.

My friend, the longtime Rights of Nature attorney Terry Lodge, describes this victory as “fragile” in his forthcoming reflection on the suit. He describes significant barriers that remain, such as a likely challenge in State Supreme Court, the nature of the law in question which only requires that environmental impacts be considered (not mitigated or avoided), and the fact that the constitutional mechanism at question in this lawsuit is only present in a few U.S. State Constitutions. He concludes that “this is the beginning, not the end” of the battle.

Whether in Bellingham, in Utah, in Alberta, at Standing Rock, or elsewhere, legal approaches to stopping the destruction of the planet have not yet been sufficient. To emphasize what I wrote earlier: most destruction of the planet is legal, and much of it is actually encouraged through various subsidies, loans, and incentives.

This is why I remain convinced that transformation of our society relies on a multitude of strategies working in concert: lawsuits, legislative change, international ecocide law, rights of nature, non-violent civil disobedience, hunger strikes, education, eco-sabotage, and even more. This is far from a passive process. Non-violent social change strategist Gene Sharp describes non-violent resistance as a form of political warfare, in that it involves the matching of forces, consideration of tactics, seeking of advantages, “battles,” and so on. [19] To effectively push our goals forward, legal fights must be integrated into vibrant, radical movements that cross political, class, and racial lines to build power and recreate society with a new, biocentric vision.

Back in Utah, looking out across a landscape that might soon be a wasteland, the setting sun casts waning light on the treetops. A small herd of Elk climbs a ridge in the distance and disappears into the foliage. Overhead, wispy clouds fade from red to deep purple, then the sky goes black. Birds sing their goodnight songs, and the stars begin to appear, thousands of them, lighting up the night sky and casting a dull glow across the countryside.

The bats are out, flitting about snatching insects out of midair. I can hear their voices. Tiny voices carrying across miles to whisper in my ear like the tickle of a warm breeze. It sounds like they are speaking. “Fight back,” they say. “This is our home. We need your help.”

[1] Dworkin, Andrea and MacKinnon, Catherine A. “Pornography and Civil Rights: A New Day for Women’s Equality.” Minneapolis: Organizing Against Pornography, 1988.

[2] “Worldwide Extraction of Materials Triples in Four Decades, Intensifying Climate Change and Air Pollution.” International Resource Panel, U.N. Environmental Programme. July 20, 2016.

[3] “Media Release: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating.’” Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. May 6, 2019.

[4] Kaplan et. al. “The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of Europe.” Quaternary Science Reviews, September 28, 2009.

[5] Bentley, Mushalik, and Wang. “The Resource-Limited Plateau in Global Conventional Oil Production: Analysis and Consequences.” Biophysical Economics and Sustainability, 2020.

[6] Nikiforuk, Andrew. Tar Sands: Dirty Oil and the Future of a Continent. Greystone Books, 2010.

[7] Bellingham Olympic Pipe Line explosion – 10 years later. Department of Ecology, State of Washington. https://ecology.wa.gov/Spills-Cleanup/Spills/Spill-preparedness-response/Responding-to-spill-incidents/Spill-incidents/Bellingham-Olympic-Pipe-Line-Explosion.

[8] Bellingham Municipal Code 2010-18 and 2010-19.

[9] Wynne, Ryan. “City of Bellingham steers away from tar sands oil,” Bellingham Business Journal. June 9, 2010.

[10] Morris, Jane Anne. “Help! I’ve Been Colonized and I Can’t Get Up!” Deep Green Resistance News Service. 2005. https://dgrnewsservice.org/resistance-culture/movement-building/help-ive-been-colonized-and-i-cant-get-up/.

[11] Personal communication, Colorado Riverkeeper J. Weisheit, September 10th, 2014.

[12] Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide. Stop Ecocide Foundation. June 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ca2608ab914493c64ef1f6d/t/60d7479cf8e7e5461534dd07/1624721314430/SE+Foundation+Commentary+and+core+text+revised+(1).pdf

[13] Bastiat, Frederick. The Law. 1850.

[14] Tuttle, James. “Frédéric Bastiat: Two Hundred Years On.” Center for a Stateless Society. June 30th, 2013. https://c4ss.org/content/20064

[15] Protect Thacker Pass. https://www.protectthackerpass.org/

[16] Hamilton, Bruce. “David Brower: Remembering the Archdruid.” High Country News. November 20, 2000.

[17] Hornick, Brad et. al. “One, Two, … Many Green New Deals: An Ecosocialist Roundtable.” Resilience. February 26, 2019.

[18] “Millions Of Barrels Of Oil Safely Reach Port In Major Environmental Catastrophe.” The Onion. August 11, 2010.

[19] Sharp, Gene. “Social Power and Political Freedom.” Introduction by Senator Mark O. Hatfield. Porter Sargent, 1980, pp. 195–257.

Thank you for your important work in standing up for our fellow non-human beings and swearing allegiance to the living Earth as a priority that stands above and apart from any allegiances to flags, legal systems or nationstates. As an author working within the Permaculture and Regenerative Gardening education fields I have recently attempted to highlight the aspects of our current legal, economic and government systems which are antithetical to the Permaculture Design Ethics.

In my recent essay I outlined 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐈𝐧𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐆𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐒𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐍𝐨𝐭 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐏𝐞𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐄𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐬𝐬. I feel this ties into your highlighting how Ecocide is Legal in our current system of government so I will share the essay below for anyone interested in learning more.

https://gavinmounsey.substack.com/p/why-involuntary-governance-structures?

Thank you for sharing your love with our Mother Earth and for giving a voice to those beings that cannot speak for themselves. You do our human (and non-human) family a great service through your meaningful works.

Appreciate you pointing out that ecocide is legal. Not only that, but it is tax exempt as well.