How to Stop Worrying and Love the Bulldozer

The mainstream environmental movement is unintentionally re-creating Dr. Strangelove, a cautionary tale about the perils of unexamined beliefs and one of the greatest films in cinematic history

In Spring of last year, I was sitting on top of an excavator in Nevada as part of a protest against the destruction of a biodiverse and sacred Native American cultural site and wildlife habitat.

That’s me in the photograph on the right. I’ve climbed on top of the machine as part of a prayer action led by Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone indigenous elders seeking to protect Thacker Pass, known in Paiute as Peehee Mu’huh, from an open-pit lithium mine.

Because lithium is a key ingredient in batteries for electric cars, this fight has represented a flashpoint in the environmental movement.

At the same time as we were sitting in front and on top of the machinery, Mother Jones Magazine was publishing the polar opposite message on its cover. I know I have a few sight-impaired readers, so allow me to explain. The cover of the May/June 2023 issue of Mother Jones features a title story called "Yes in Our Backyards: It's time for progressives to fall in love with the green building boom," written by Bill McKibben.

The cover of the magazine shows a woman standing in the bucket of an excavator that closely resembles the one I climbed on top of at Thacker Pass. But this woman is not protesting. Instead, she is embracing the machine lovingly, a rapturous expression on her face.

Welcome to Biocentric, a newsletter focused on sustainability, greenwashing, and building a resistance movement to defend the planet. I’m Max Wilbert, co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass and co-author of ‘Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It.’ Biocentric subscriptions are free, but paying for a subscription supports the community organizing work you read about here, and gets you access to behind-the-scenes information and unreleased drafts.

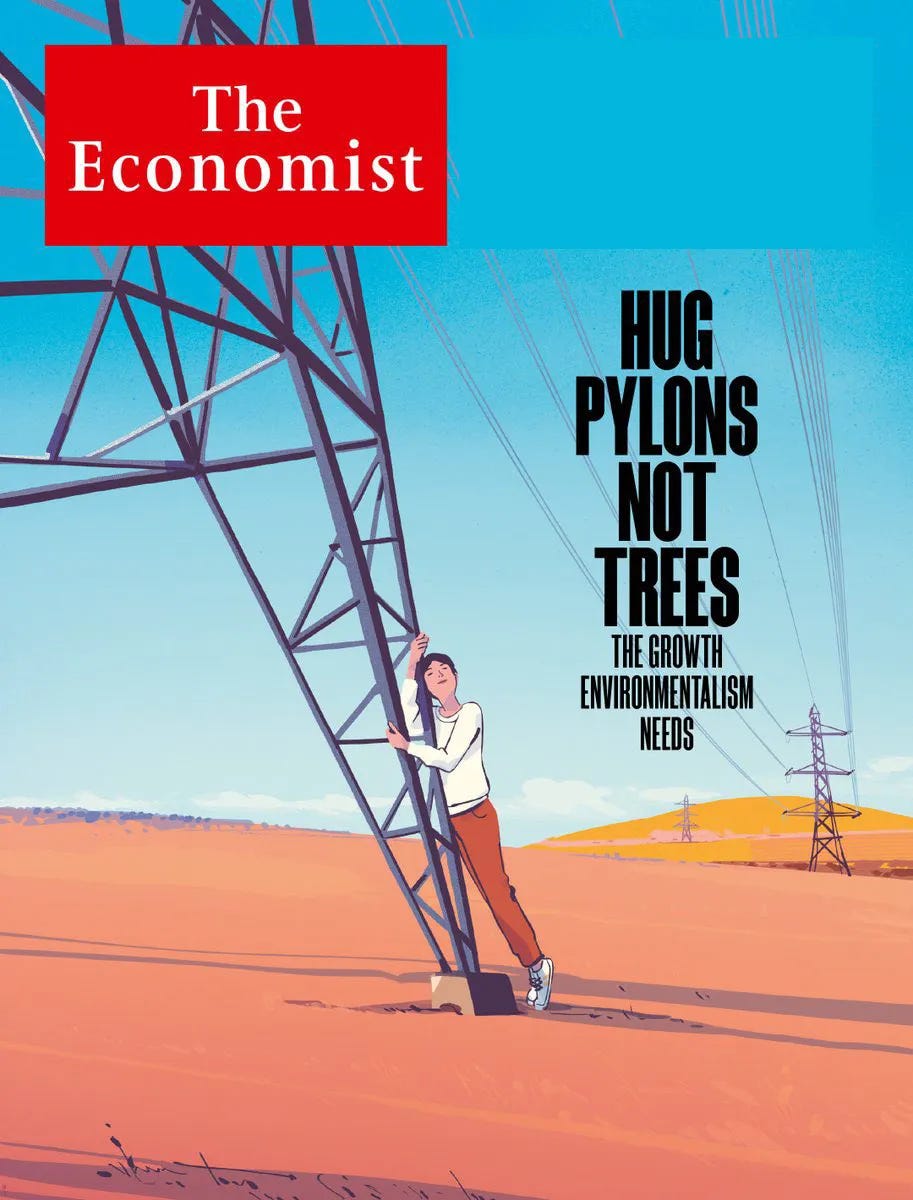

Around the same time, the Economist magazine published a similar image to accompany their cover story titled, “Hug pylons not trees: the growth environmentalism needs.” The artwork shows another person embracing a machine — this time, the bottom of a high-voltage electrical transmission line pylon — a similar expression of bliss on their face.

The dichotomy between these images represents a profound division within the environmental movement.

On one side, mainstream environmentalists and large organizations (such as McKibben’s 350.org, Mother Jones, the Economist, The Sierra Club, and many others) are advocating for a wholesale transition of the industrial economy as it currently exists to being powered with renewable energy technologies.

This would entail a gargantuan expansion in solar and wind energy production (and electrical transmission lines to carry this energy), a wholesale shift from gas and diesel vehicles to electric cars, and the electrification of everything from steel and concrete production — both very dependant on fossil fuels and highly polluting — to the heating of homes and office buildings.

They tell a tempting story: by swapping out the energy sources powering society, we can solve global warming while simultaneously boosting business, creating jobs, and achieving prosperity.

But like most fairy tales, the story is not just false — it obscures a grim reality.

Perhaps the most prominent scientist promoting this energy transition is Mark Z. Jacobson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford, who has created detailed plans on how to transition to 100 percent renewable energy by 2030.

I wrote about Mark Jacobson and his proposals in my book, Bright Green Lies, How the Environmental Movement Lost its Way and What We Can Do About It. There are two main problems with his work. The first is that his research, in the words of a group of 21 scientists and engineers who reviewed it, “involves errors, inappropriate methods, and implausible assumptions.” In one of Jacobson’s models, hydropower increases by 15x in the United States by 2055. Critics say that would be disastrous for aquatic creatures and also point out that this is “physically impossible.” Jacobson’s response has generally not been to prove his critics wrong, but rather to sue them for millions of dollars (his lawsuit was ultimately dismissed as frivolous and he was ordered to pay attorney fees).

The second problem? This vision of a green energy transition isn’t green at all

Producing wind turbines, solar panels, electric vehicles, geothermal power plants, and other forms of green technology requires huge amounts of steel, aluminum, copper, composites, balsa wood, rare earth elements, cobalt, nickel, and other materials.

Extracting these raw materials causes significant habitat destruction and pollution, and is entirely dependant on fossil fuels. One study — the most comprehensive ever conducted on the topic — found that “Extractive industries are responsible for half of the world’s carbon emissions and more than 80% of biodiversity loss.”

Around the world, grassroots environmentalists, frontline communities in the Global South and the hinterlands of the Global North, and indigenous peoples are standing up against “green” industrial projects which represent further destruction of habitat, pollution of air and water, and extinction of species.

Here’s 22 examples:

In Colombia, Wayúu peoples are opposing industrial wind energy development

In Scandinavia, Sámi people are resisting mining and wind power projects

In occupied Western Sahara, Sahrawi people are fighting “blood renewables” and phosphate mining (phosphate is a key element in many EV batteries)

Members of the Yakama Nation are standing up against “green” energy storage projects in Washington

Russians are fighting “green” nickel mines in Siberia which are devastating the environment

In Australia, the aboriginal Jirrbal community is opposing wind power to protect the Chalumbin wilderness

Organizers in Nevada are fighting massive solar energy projects in the Mojave desert

In Chile, opposition to mining (increasingly for “green” energy minerals like copper and lithium) is widespread and growing

Hawaiians have launched major protests against wind energy projects

Radical environmentalists like myself, alongside Paiute and Shoshone people, have fought against the Thacker Pass lithium mine

Argentinian indigenous communities have launched a mass protest movement against lithium mining

Grassroots environmentalists in Vermont used civil disobedience to try and stop the destruction of Lowell Mountain for a wind energy project

In Portugal, lithium mining corporations are using counterinsurgency techniques against local communities

Communities throughout the United States have resisted solar projects due to harm they would cause to forests and other wild areas in Maryland, Virginia, and dozens of other locations

In Hungary, local communities have risen up against a massive battery manufacturing factory. Opposition to major factories for EVs and green tech production is widespread around the world, including in Germany

In occupied Tibet, Chinese corporations are poisoning rivers and leaving behind ecological wastelands while local people are run roughshod

Indigenous communities and civil society organizations in Indonesia are fighting greenwashed mining projects for electric vehicle batteries

Communities on the US East Coast have risen up against offshore wind energy development over threats to fish and whales

Geothermal energy projects are facing widespread opposition in the places where they are being implemented, such as Nevada, Iceland, and Kenya

Significant opposition to wind energy and new transmission lines has arisen in Germany over threats to protected forests

Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache communities in Oklahoma are fighting a refinery for nickel, cobalt, and other minerals used in “green” technology

The Yurok Tribe, Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria, Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw, and the Tolowi Dee-ni’ Nation have passed resolutions opposing offshore wind energy projects in California and Oregon

Bill McKibben’s answer? Buy off the opposition.

The work that Bill McKibben (author of the Mother Jones article) has done to publicize the dangers of global warming is incredibly important. But our disagreements are profound. For example, McKibben proposes that we overcome local and grassroots resistance to “green” energy and mining projects by giving “locals a stake in the economic success of the enterprise.”

In other words, he thinks corporations and government should bribe them.

The great American scholar Lewis Mumford, in his book “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics,” wrote of the moral decline that comes when a society invests all its energies toward industrial production.

People in energy-addicted societies receive “every material advantage, every intellectual and emotional stimulus [they] may desire, in quantities hardly available hitherto even for a restricted minority: food, housing, swift transportation, instantaneous communication, medical care, entertainment, education,” Mumford wrote. This, he says is “a magnificent bribe… that threatens to wipe out every other vestige of democracy.”

“More of this,” says McKibben: bribe populations so they don’t fight when their mountains are blown up, their deserts paved with solar panels, their water poisoned for lithium mines, and their oceans dotted with skyscraper-sized wind turbines.

As “green” energy projects proliferate, their impacts become more obvious and resistance becomes more common.

When my friend Will Falk and I first set up our protest camp on the site of the proposed Thacker Pass lithium mine in January of 2021, we set two goals for ourselves. The first was to stop the mine and protect the land. The second was to raise awareness of the harms of so-called green technology and shift the culture of society in general and especially the environmental movement towards opposing these projects and standing with the natural world.

We failed in the first goal.

Despite setting up a protest camp on the site, bringing thousands of people to visit the land and fall in love, organizing in the community to hold protests and submit detailed public comments and concerns, speaking with government officials, including the president himself, filing lawsuits in federal court, contesting permits, and taking nonviolent direct action, Thacker Pass is currently being destroyed.

Seven land defenders, including myself, have been sued by the mining company.

But our second goal has been at least partially successful.

The story of our resistance at Thacker Pass has gone around the world. Millions upon millions of people have been exposed to biocentric perspectives on this debate because of our work. And I know for a fact that we have inspired others to launch similar campaigns.

The “green economy” is a case of the Shock Doctrine coming to life

In his Mother Jones article, Bill McKibben writes:

“I’m an environmentalist, which means I’ve got some practice in saying no. It’s what we do: John Muir saying no to the destruction of Yosemite helped kick off environmentalism; Rachel Carson said no to DDT; the Sierra Club said no to the damming of the Grand Canyon... In a world where giant corporations, and the governments they too often control, ceaselessly do dangerous and unnecessary things, saying no is a valuable survival skill for civilizations.

But we’re at a hinge moment now, when solving our biggest problems—environmental but also social—means we need to say yes to some things: solar panels and wind turbines and factories to make batteries and mines to extract lithium.”

One of the first rules of debate is that if you can slide a premise past someone, you’ve already won. That’s one of the tricks used by Bill McKibben in this piece, and also in his similar 2021 article in The New Yorker, “The Shift to Renewable Energy Can Give More Power to the People.”

In that piece, McKibben begins by writing of how people fall in love with nature and want to protect it. But this leads straight into his rhetorical trick. McKibben writes, “there’s one trapdoor here: if we’re going to build out renewable energy in the ways that the climate crisis requires, it’s going to require intruding on some of that landscape.”

There are two premises being slipped past us here. First, McKibben is arguing that building out renewable energy is going to require “intruding on” (aka destroying) land. And second, that renewable energy is necessary to stop the climate crisis.

The first argument is unequivocable. The planet is already paying a price for green technology, and the bill is set to rise steeply. Electric vehicles still only account for 15-20% of new car sales (and most car sales are used; in the U.S., about three times as many used cars are sold as new cars), and wind, solar, and geothermal energy make up just 5.8% of U.S. energy consumption.

As those numbers rise, more desert habitat will be bulldozed, more forests cut down for wind turbines, and more mountains will be blown up for minerals. As a Vox headline put it, “Reckoning with climate change will demand ugly tradeoffs from environmentalists — and everyone else.”

This, to paraphrase Mumia Abu Jamal, “is the Shock Doctrine come to life.”

Can renewable energy stop global warming?

McKibben’s second and core argument is that replacing fossil fuels and solving global warming requires building renewable energy out as quickly as possible, and therefore some destruction is justified.

Setting aside the human-supremacist thinking inherent in this (nature, after all, would prefer to neither be bulldozed for solar energy or destroyed by global warming. And nature does not give a damn about whether or not we have electricity), the premise doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Around 2014, a team of Stanford scientists hired by Google to research green energy technologies came to a startling conclusion. “Even if every renewable energy technology advanced as quickly as imagined and they were all applied globally,” they wrote, “atmospheric CO2 levels wouldn’t just remain above 350 ppm; they would continue to rise exponentially due to continued fossil fuel use.”

Real world data backs this up. After analyzing data from 128 nations, Richard York, a researcher at the University of Oregon, found that:

“the average pattern [in energy use] ... is one where each unit of total national energy from non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-quarter of a unit of fossil-fuel energy use and, focusing specifically on electricity, each unit of electricity generated by non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-tenth of a unit of fossil-fuel generated electricity.”

In other words, when you build solar panels and wind turbines, it barely reduces the amount of fossil fuels being burnt. York concludes: “These results challenge conventional thinking ... they indicate that suppressing the use of fossil fuel will require changes other than simply technical ones.”

We can see this in the world today. As the deployment of renewable energy technologies have increased dramatically over the past decade, carbon emissions have only risen higher. Fossil fuel emissions are at record-highs, and oil industry is backing out of prior energy transition plans.

McKibben’s plan—building out green energy as quickly as possible, and don’t worry about harm to the natural world—isn’t working.

Instead, we're getting all of the catastrophic harms of global warming and the fossil fuel industry combined with the massive ecological damage associated with mining raw materials, manufacturing, and installing an entire new “green” energy infrastructure in a fatally-flawed and ultimately doomed attempt to replace keep industrial civilization running “business as usual” for just a little while longer.

As my friend

wrote in her newsletter , belief in so-called “green growth” is a new form of climate denial. “Instead of denying the science of climate change,” she says, “'green growthers' are now denying the mitigation required to avoid the worst impacts of a hotter planet.”In other words, green energy will not solve global warming and will not save the world. Far more is needed. Global warming is a very serious issue, and the fossil fuel industry — along with logging, industrial agriculture, and steel and concrete production — account for the vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions. But we should never forget that greenhouse gases are just one of the industrial assaults levied on the living planet by modern industrial culture.

We are living in the 6th great mass extinction event in Earth’s history. Ecological studies have demonstrated that by far, most of the species extinctions on the planet are being driven by habitat destruction and direct killing of wildlife, not global warming (at least, not yet).

Environmental groups and governments today focus overwhelmingly on climate change. Overfishing, soil erosion and desertification, urban sprawl, oceanic dead zones due to fertilizer and factory farm runoff, and the felling of the last old-growth forests often seem forgotten. In our rush to reduce carbon, precious wildlife habitat is being sacrificed to “green growth.” This forgetting is a real danger.

A recent headline reads: “Like fracking under Obama, mining poised to grow during Biden years.” Three years into Biden’s term, that prediction is coming true. In Nevada, the driest state in the union, scarce groundwater is being depleted at a rapid pace to serve the mining industry, and new lithium mines to serve the EV and battery energy storage market are destroying thousands of acres of old-growth sagebrush habitat, and the golden eagles, pygmy rabbits, pronghorn antelope, burrowing owls, and sage-grouse who depend on this land. And if the mining industry consumes mountains and water, it excretes toxic waste – more than any other industry on the planet.

Can we mine our way to a sustainable world? I think not. Ultimately, it matters little whether habitat is paved over for roads that will be traversed by electric vehicles, or fossil fuel ones. Destruction is destruction, and we won’t drive—or buy—our way out of this crisis. Only by addressing the roots of the problem can we begin to find real solutions.

This is exactly what McKibben fails to do. As my friend Suzanna Jones, who was among those arrested protesting Enbridge’s Lowell wind energy project in Vermont in 2011, wrote:

“sadly, McKibben studiously avoids criticizing the very economy he once fingered [in his 2008 book Deep Economy] as the source of our environmental crisis. During his talk he referred to Exxon’s ‘big lie’: The company knew about climate change long ago but hid the truth. Ironically, McKibben’s presentation did something similar by hiding the fact that his only ‘solution’ to climate change – the rapid transition from fossil fuels to industrial renewables – actually causes astounding environmental damage. Solar power, he said, is ‘just glass angled at the sun, and out the back comes modernity.’ But solar is much more than just glass.

More than just glass, indeed. To supply one silicon smelter in Washington State, permitting documents revealed a supply chain including “900 million kilowatt hours [of electricity], 170,000 tons of quartzite rock (silicon dioxide), 150,000 tons of blue gem coal and charcoal, and 130,000 tons of wood chips” resulting in “766,000 tons of greenhouse [gas emissions] per year, plus tens to hundreds of tons of other coal toxins”. And that’s just to produce the silicon component of solar panels. The supply chains for the steel, aluminum, lead, silver, copper, and other materials found in PV panels, substations, and transmission lines are similarly polluting and extractive.

NIMBY to NOPE

Even the title of McKibbin's article, "Yes in Our Backyards," is very telling. There was a time when so-called "Not In My Backyard" activism or "NIMBYism," was regarded as an honorable and righteous thing. It was associated with people and communities fighting back against corporations who sought to bring polluting, dumps, recycling facilities, smelters, mines, factory farms, oil refineries, and incinerators into neighborhoods. Most early NIMBY fights in the environmental movement arose as poor communities, often communities of color, rose up to protect their health against corporate and government overreach. The environmental justice movement and NIMBY campaigns have overlapped significantly for decades.

In 1994, anti-corporate-power activist Jane Anne Morris wrote a book called “Not In My Backyard: The Handbook,” The first page of the forward reads:

“NIMBY campaigns are often inconvenient thorns in the sides of larger movements that have master plans outlining what is good for other people.”

This, of course, describes Bill McKibben's perspective exactly. He is the leader of a larger movement, 350.org, which has received tens of millions of dollars in funding from large foundations. There are many good people involved in 350, and I call some of them friends. But the policy of that organization is quite misguided. They have, to use Morris’ language, a “master plan outlining what is good for other people” — namely, solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, battery factories, and the mining necessary to produce these products on a grand scale.

In this sense, McKibben is a perfect example of what Latin American sustainability scholar Miriam Lang described when critiquing the false promise of Correa administration programs in Ecuador:

[His policies represented a false development in which] “so-called ‘human needs’ [such as massive energy production] continue to be established from above, in a way that is colonizing, technocratic, undemocratic, and definitely not intercultural, while taking into account neither the voices nor parameters for welfare of indigenous peoples and other culturally different groups.”

In another paper, Liang describes McKibben-style energy and mining policies as:

… hegemonic answers to climate change centered on green growth and leading to a considerable intensification of extractivist pressure on regions of the Global South… Instead of a real energy transition, this rather translates into an overall energy expansion — a new driver for economic growth.

There are other acronyms that perhaps more accurately reflect the views of most people opposing green energy projects: NIABY — Not In Anyone’s Backyard, or perhaps my favorite: NOPE — Not On Planet Earth. Personally, I am proud to be a NOPE activist: I oppose industrial energy development, mining, and the fossil fuel industry everywhere on this planet.

“How I stopped worrying and learned to love the bulldozer”

For any young people who haven't seen the film, “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” it is considered one of the greatest films of all time.

A timeless classic in its critique of warmongering politicians and hawks, the film explores the insanity underlying the phenomenon of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) during the nuclear brinksmanship of the Cold War.

In our modern era, the ethical conundrums and mind-numbing absurdity of creating technologies that threaten the entire world are just as relevant to the ecological crisis as to the nuclear threat which has never gone away (in fact, today's war in Ukraine and genocide in Palestine means the nuclear stakes are higher than they have been in decades).

There is a certain Dr. Strangelove quality here. McKibben’s Mother Jones piece could just as well have been titled “How I stopped worrying and learned to love the bulldozer.” From being a leading voice exposing the dangers of global warming and speaking out against the insanity of endless growth, he has become a booster for a certain sector of the industrial economy that is highly profitable and is experiencing the very sort of explosive growth at the expense of nature and communities that he once critiqued.

McKibben has learned to stop worrying and love the bulldozer, and in doing so, has become a cautionary tale for us all.

As my friend Suzanna wrote in another piece:

Unfortunately, Mckibben’s “environmentalism” is no longer about protecting the land... It is about sustaining the comfort levels that Americans feel entitled to... It is entirely human-centered and hollow, and it serves corporate capitalism well. This version of environmentalism has been successfully mainstreamed, but at the cost of its soul.

Another friend,

, saw McKibben live not too long ago and this was her reflection:When climate change activist Bill McKibben spoke last month in Santa Fe about climate change and the green building boom, he said that instead of a not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) mentality, people should welcome solar panels and wind turbines. “Don’t be the person who hires a lawyer,” McKibben said, “and gets in the way of the future.”

I could not disagree more.

If “the future” means more machines and more mountains destroyed, more greenwashed energy projects, mines, and pipelines as the planet burns, more sacred sites destroyed and more water poisoned, more land defenders criminalized and corporate power ascendant, then getting in the way of the future using every strategy and tactic we can imagine is the most important thing we can be doing.

Comments are welcome. Please consider subscribing and hitting the ♡ button to help more people find this post.

Thank you for this important and well-argued critique of McKibben and his ilk.

Is the "Carbon Tunnel Vision" graphic yours? It's very good at illustrating the myopia of mainstream environmental narratives. All environmentalism has been reduced to climate issues and climate issues have been reduced to carbon. The other contributor to climate change is land use, but that gets left out because it can't be monetized, and addressing it would mean addressing industrial civilization. It's a big scam for sure.

Excellent article, as always. I was hoping you might have spent a little more time mentioning one other thesis that McKibben tossed into his article. That we need the same amount of energy as we are currently using. It is so important for those of us in the rich part of the rich world to accept that we will have to consume much less. We will either have degrowth soft landing or a hard landing.