I’m Max Wilbert, the co-author of Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It and co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass. Welcome to Biocentric, a newsletter about sustainability, greenwashing, and resistance! If you want to follow this newsletter, you can subscribe. Almost all the writing I publish here is free, but paid subscribers support my writing and organizing, and receive occasional behind-the-scenes reports and unreleased drafts.

If you had met my grandmother, you wouldn’t forget her. Five feet tall, with short white hair, her face was creased with deep smile lines and her hands were bony.

She often wore turquoise glasses, dangling earrings, bright red basketball shoes, pastel blouses, and polka-dot pants. I knew her as “Bama”—a nickname my cousin gave her.

Some of my childhood memories involve Bama teaching my sister and I to paint along Lake Washington in Seattle, or visiting her house and running to check the secret hiding place she kept stocked with “White Rabbit” candies wrapped in rice paper for visiting kids.

Bama often wore bundles of necklaces with Buddhist, Hindu, and Christian symbols. Not long before she died at age 92, someone asked her what she believed in. She answered “I believe in art, and I believe in people.”

I’ve been reflecting on her words ever since.

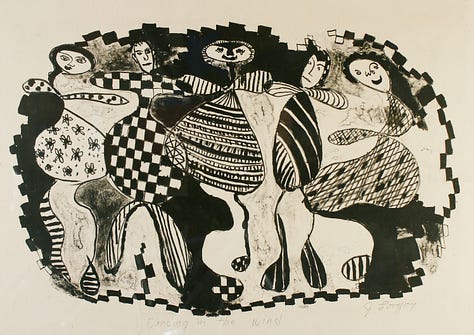

Art is usually defined as something humans create for beauty: sculpture, music, literature, dance, drawing, poetry. My grandmother herself was an artist, creating hundreds of colorful paintings and collages for more than 60 years.

But this is too exclusive. Art is not only human. Birds of Paradise arrange colorful natural objects in stunning arrays. Octopuses put fashion designers to shame. Wildflowers paint entire mountainsides. Then there is the non-living art of our planet: the meandering of braided river channels; geological forces squeezing stone into gems; ancient sand dunes coalescing into stone under vast pressure; then eroding back into sand one grain at a time. What are the miracles of photosynthesis and the hydrological cycle, if not art? And that’s only to speak of our planet. Look through a telescope and you will see that art is a property of the cosmos.

My grandmother saw beauty everywhere: in her chrysanthemums; in her grandchildren; in strangers on the street; in a well-made meal; in a great hand of cards (and in her own laughter at her shameless cheating).

Perhaps to believe in art is to believe that beauty is a characteristic of the universe. I think this is what my grandmother meant: that art is a fundamental property of matter as basic as gravity or nuclear cohesion. That life is an aesthetic experience, and that one way to describe the purpose of life is that it is to create—or rather, participate in the unfolding creation of—art. To align ourselves with beauty.

Bama loved basketball, and she taught me to love the game, too. Sitting around her old TV, watching Ray Allen shoot silky elbow jumpers, she used to say “he is as graceful as a dancer.” I’ve watched basketball ever since. Recently, I’ve been reading about the legendary coach John Wooden, who led UCLA to ten NCAA championships in 12 years. Wooden got the best out of his teams through a unique teaching philosophy. He never spoke of winning and losing, but only of effort. He told his players, “make each day your masterpiece.” He was telling them to make each day a work of art; to live artfully.

My grandmother lived in this way. She immersed herself in art and lived in a world brimming with meaning and beauty.

The second part of my grandmother’s belief—her belief in people—has been harder for me to understand.

Art is one thing, but people are another. Growing up, I didn’t trust easily. For most of my life, I’ve been more content alone than in a group of people. And as someone in love with our planet and working to stop mass extinction, the climate crisis, toxic pollution, and other ecological problems, it’s easy to veer into misanthropy.

It is easy to think we are simply a broken species.

That belief is incredibly common. No wonder we numb our pain with drugs, alcohol, pornography, social media, video games, sugar, and other addictions. If we are broken, then nothing can be done.

There is no denying that spiritual illness, exploitation, and cycles of trauma dominate our society. Renape/Lenape scholar and activist Jack D. Forbes writes in his book Columbus and Other Cannibals that “The disease that is overrunning the world is the disease of aggression against other living things and, more precisely, the disease of the consuming of other creatures’ lives and possessions.” Forbes describes colonization and imperialism as the spread of this “wetiko psychosis,” but he does not argue that this is racially determined. Rather, he believes that the potential for great evil—ecocide and genocide—is latent within all people, but that certain societies systematize and encourage this destructiveness.

There is no shortage of evidence that humans are destructive. But the older I get, the more counter-examples come to mind. I recall sitting and drinking a cup of tea with my grandmother. I spend time playing with my 3-year-old nephew—a budding biologist who instinctively does what David Abrams calls “becoming animal.” I walk through dark forests, gathering mushrooms into a basket woven by my aunt of cattails and spruce root and sweetgrass and spreading their spores as I wander.

I rejoice at stories of people defending land and biodiversity. I think of friendship, loyalty, courage, wisdom, reciprocity, compassion, and all the other traits that we reveal in our best moments.

The narrative of humans as broken fails to account for us at our best. And so, I am following in my grandmother’s footsteps. I am coming to believe in people; in our ability to change; in our ability to do what is right.

Beauty, Forbes argues, is created only by conscious effort and deliberate shaping of human culture around life-affirming ideals. While simple in concept, this is exceptionally challenging in reality. It’s why I’ve said that the most complex human technology is not a nuclear reactor or spacecraft, but rather something far more nuanced: the social knowledge held by elders that allows them to shape and guide a human culture towards long-term sustainability.

Besides being wrong, misanthropy is simply not a viable political strategy. Mistrust too easily becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, a spiral that only leads deeper into a world of isolation. We give each other, and ourselves, too few chances to live up to our potential. To make change, you must at least to some extent believe in people, as my grandmother did.

As Antonio Gramsci wrote, “The challenge of modernity is to live without illusions without becoming disillusioned.”

Clean water, intact habitat, a living planet, and the beauty which emerges from this are essential to the human mind, body, and soul. So are other human beings. If there is any path to a better future, we will walk it together. And for all the trauma and injustice in this world, many of us still strive to repair, to heal, to harmonize.

Art, and people. It turns out, I believe in them too. Tears roll down my cheeks. My grandmother is still teaching me, although she has been gone for twelve long years.

Obituary

Jean Elizabeth Lovejoy Smith is out of this world, leaving a trail of profound sparkle.

Everywhere she went, people smiled at her and said, "I want to look like you when I'm your age." She died with her black nail polish with white dots on it on her fingernails.

Jean was born October 18, 1919 and died October 28, 2011. Jean was known to her grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and to many as “Bama.” She said what needed to be said but in the kindest way. Mostly, she always believed in everyone, always believed there was hope, and said, "people need each other."

She loved to cook, watching the early Julia Child cooking shows and taking notes. She could make a gourmet meal in a snap out of nothing. In the school days of her daughters, she made 6 lunches every day (often including a hard-boiled egg with a note or a face on it). She made the best pies ever; she was famous for baking dad's favorite cake after she had sideswiped the car.

Jean was an active supporter of the civil rights movement in the 60s, taking her kids out of school and placing them in Freedom School to support desegregation in the South. One daughter remembers, during the Vietnam war, skipping school to join an antiwar protest. She ran into Jean at the march, who understood the protest was more important than a day of school.

Jean returned to work as an RN after 20 years of raising kids, working with the elderly and mentally ill, always coming home with stories that were often hilarious. She loved animals, domestic and wild. She was an avid sports fan who particularly loved watching the Seattle Sonics, baseball, and Tiger Woods. Two summers in a row, when she was 87 and 88, she backpacked 5 miles out to the Washington coast and camped on the beach with her family.

Although a small woman in stature, she was bold on canvas. She had big artistic vision and created art throughout her life: ceramics, oil painting, acrylics, collage. She was an artist in every area of her life, from the way she decorated her home to the stylish, sometimes outrageous way she dressed. Bama Jean lived life fully. On her last day of life she had a great day: delivered prizewinning chrysanthemums to the mum show, ate Mexican food for dinner, watched the world series and Project Runway with her family, and went to bed happy.

You are such a great writer max! Thanks for sharing your art with the world.

With words as your pigment, you painted a great artist. In her footsteps, indeed! Thank you Max!