Remembering the Lost Giants

Reflecting on shifting baseline syndrome and the fact that redwoods aren't the tallest trees on Earth: they're the tallest which haven't been logged.

The Czech and French author and political dissident Milan Kundera once wrote that “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” Although he wrote about the authoritarianism of the Soviet Union, Kundera’s insight could equally be applied to any totalitarian state, or to the industrial system that is tearing through the ecology of our planet. For any genocide, ecocide, or atrocity to be complete, it must be buried.

This is why the Turkish Government to this day perceives discussion of their genocide of the Armenian people to be a threat to national security. It’s why the full details and reverberations of the shameful legacy of slavery and the holocaust of indigenous people are not taught in American schools. It’s why Israeli society must deny the existence and significance of the Nakba and pretend that their holy land was “Terra Nullius” reclaimed in a War of Independence sanctioned by god. And it’s why the ongoing devastation of planet Earth by industrial civilization isn’t suitable for polite conversation, let alone detailed study. Societies built on a foundation of unspeakable acts do not wish to be reminded of these facts.

This is closely linked to what is called, in ecology, “shifting baseline syndrome.” It refers to the fact that ecological change which is happening exceptionally quickly according to the clock of nature, still takes place over decades or centuries. As a result, human beings can lose sight of what is ecologically normal. This syndrome makes it dangerously easy for us to lose track of rate and scope of the ecological collapse we are living in.

Memory is important. Remembering atrocities means we are forced to grapple with their implications in our society and our lives today, and compelled to take moral action to right historical wrongs. This is a difficult process not just because it challenges individual privilege, but because it means challenging the most entrenched, dominant, and violent systems of power on the planet.

All of this brings us to trees. It’s a familiar fact to many people that the Redwoods of Northern California are the tallest trees in the world at nearly 400 feet.

This is both true and false. It’s true because right now the redwoods are the tallest trees on Earth. But it’s false because not long ago, there were taller trees to be found, but they were all cut down during the heyday of old-growth logging in the Pacific Northwest.

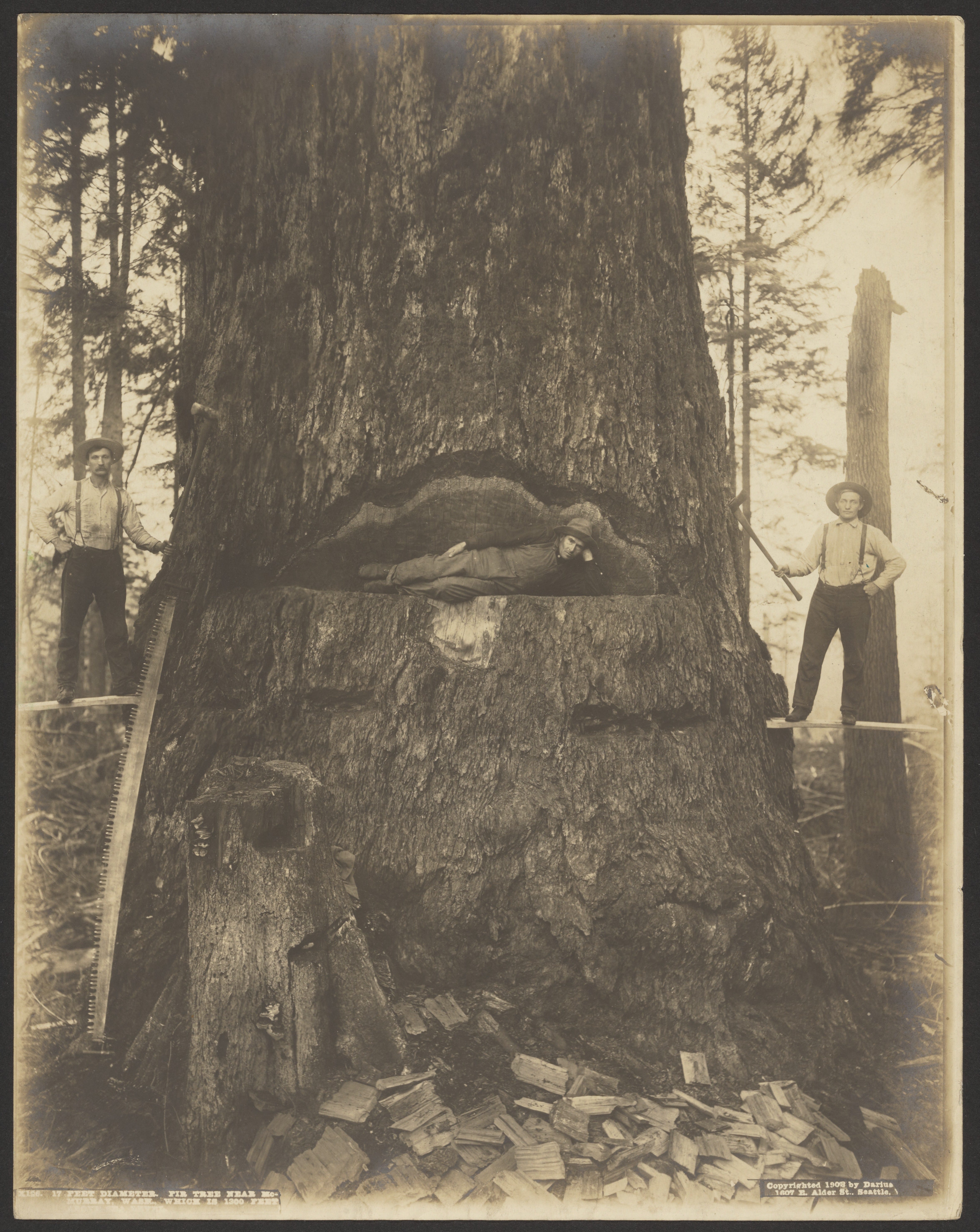

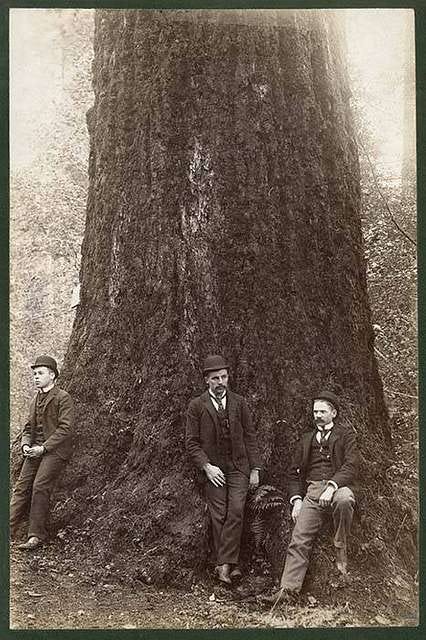

The tallest known redwood, named Hyperion, was measured at 380.8 feet tall in 2019. But historical accounts are full of references to Douglas Fir trees 400 feet tall and more. One tree in the lower North Fork of the Nooksack River Valley (near present day Bellingham, WA) is thought to have been 465 feet tall, which would make it the largest tree ever recorded. That’s nearly the height of a 50-story building, and for comparison, the Empire State Building has 102 floors.

That tree wasn’t an anomoly. Big-tree researcher Micah Ewers of Portland writes, “If this was just a freak occurrence, I would write it off. But I’ve collected 90-100 reports of 300- to 400-foot Douglas firs. A hundred years ago, trees rivaling the height of the redwoods were fairly common. The whole Puget Sound was just filled with giant trees.”

This is Biocentric, a newsletter about sustainability, overshoot, greenwashing, and resistance. It’s written by Max Wilbert, co-author of Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It and co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass. If you want to follow, you can subscribe for free. Paid subscribers, in return for supporting this publication, our mentorship program, and the activism you see here, receive access to private posts containing behind-the-scenes reports and unreleased drafts.

Ewers continues:

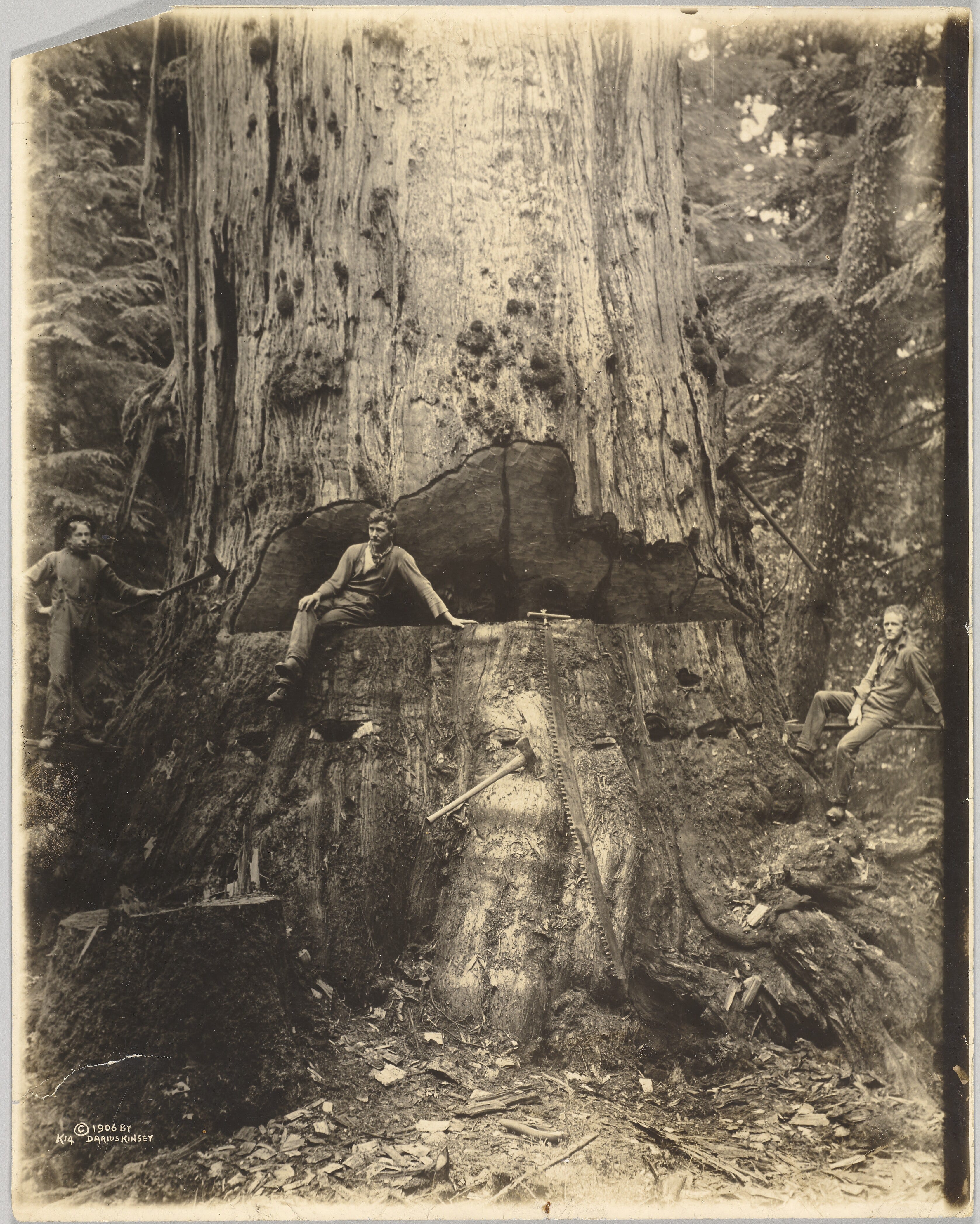

[T]he size of forest that was growing in Seattle [historically] was astounding; 250 – 300 foot trees were common. I am trying to follow up on an old report of a 412 footer said to have been logged around Tacoma, and another big tree 17.8 feet in diameter east of Seattle was reported in 1909 at over 400 feet — the tree was so big that the Puget Sound railroad had to be built around it.

Another fir tree reported in Chehalis County in 1893 was measured with survey instruments at over 400 feet tall and 17 feet in diameter. There were even reports of 300 foot cedars and 400 foot Sitka Spruce 20 feet in diameter in Washington and Oregon 100 years ago.

If you look up “Ravenna Park” in image search you can find old post cards which give the size of some of the trees that used to grow in Seattle’s most treasured city Park. Those fantastic trees were listed on the post cards as from 270 to about 400 feet in height and 10 to 14 feet in diameter. Age estimates were between 1,000 and 2,000 years for the oldest of them. Just imagine these massive old beasts jutting out of the little creek and valley near the University District.

They were all cut down for quick cash between the 1910’s – 1920’s… the excuse was that the trees were dying and needed to come down, which may have been true for one, but not the whole stand.

Same story in Vancouver, only at least Stanley Park was preserved. Wind had blown down the last of the 325 footers in the park by 1926. Portland also had some 300 – 330 footers in its vicinity, the last of them logged in the 1910’s – 20’s.

I think the Redwoods and Douglas fir were actually [roughly] tied for tallest tree. The tallest reported Redwoods I have discovered were up to 424 foot around 1886, while the tallest report for Douglas fir is 465 feet. I actually heard a story from a guy in a Gardenweb forum who claimed his father had felled a 480 foot fir in the Black Hills, near Bordeaux, Washington around 1930 — although, this is second hand, so it remains an unsubstantiated claim.

A 2008 study on theoretical limits of Douglas fir height out of Oregon State University came up with a range of 99 – 145 meters (325 – 475 feet) as the possible limits for Douglas fir, whereas a 2004 study on Coast Redwoods yielded a slightly smaller limit of 400 – 430 feet. So it may well be that Douglas fir was the supreme master of stature after all!

Redwood holds the title for now, although it wouldn’t surprise me if a few hidden giant Douglas fir, over 350 feet high, still exist hidden in some valley awaiting discovery.

The last real big fir that has survived into modernity (which has been publicly reported anyways) was the “Mt. Pilchuck giant”, fir tree cut down on October 22, 1952 near the small town of Verlot, Washington [located 20 miles east of Everett]. The big tree, 700 years old, was reported to be over 350 foot high, 11 feet 6 inches in diameter, and 30,000 board feet.

From that point on, records are few for the big trees over that height range, except of course, the redwoods in California which have about 300 trees alive today of that height. (Impressive, considering 96% of old growth Coast Redwood has been clear-cut).

If you ever find yourself among the skyscrapers of Seattle or Vancouver, or wandering through the suburbs or young woodlands of the territory in between, take some time to reflect that where you are walking was not that long ago full of the largest trees on the planet. And ask yourself: what will it take to right this historical wrong?

Today, the few remaining old-growth forests in the American and Canadian West (and globally) continue to face serious threats. But people are organizing to protect them. I recommend people get involved in these efforts or support however they can.

In Washington State, the Legacy Forest Defense Coalition aims to protect the trees which naturally regrew after these early logging efforts and are now becoming old-growth again. They were mentioned in a previous piece here.

On Vancouver Island in western Canada, the movement to protect the old-growth forests of the Ada'itsx/Fairy Creek watershed became the largest movement of civil disobedience in Canadian history between 2020 and 2022, during which time more than 1,000 people were arrested defending the land. This forced the government to suspend logging in parts of the area for several years. The temporary protection is scheduled to expire on February 21, 2025, and more forest defense may take place. For more information, follow the Fairy Creek Blockade / Rainforest Flying Squad on social media, and read

Gavin Mounsey’s extensive history and documentation of the movement.

In the interior of British Columbia, a wonderful organization called Conservation North is working to protect inland temperate rainforest from widespread logging, including old-growth and primary forest logging.

The Tongass Rainforest in Southeast Alaska, the last great expanse of temperate old growth forest left in the United States, is facing a serious threat to its continued existence, as I documented in the post “The Biggest Threat to Alaskan Rainforests This Century.”

Save the Hoosier National Forest is fighting to protect native forests in Illinois from Forest Service logging plans.

Feather River Action and allies are fighting to stop a massive Forest Service logging plan in northeastern California disguised as “forest health” and “fire risk reduction.” See this piece for background on the greenwashing tactics being used:

Feel free to comment or message me about ongoing forest defense efforts, and I will add them to this list.

Historical photographs and modern comparisons

This piece was republished in The Orcasonian.

PS — I’m looking for a volunteer or someone interested in a trade for helping record voiceovers of these articles. They would be published here on Substack, and on the Green Flame podcast. If you’re interested, get in touch.

It breaks my heart…again and again. And when I am in Washington or Oregon and see those truck beds filled with trees, I cry. I live in Central Texas where there’s no big old growth forests or commercial forests that I know of so seeing my kin being hauled out of those forests is traumatic—for the trees and for me. Thank you for this article bringing memory of the old forests back to us.

Here's a 3-year-old, 10-minute PBS mini-documentary on the struggle to preserve the giants in Fairy Creek: https://youtu.be/mRd8_Tu7YDs Might be a good resource for folks who prefer to view and listen, rather than read (both are great, of course). Thanks, Max, for your dedicated witness. Those photos were tough to look at.