Forests and the Water Cycle

How logging contributes to global warming, worsens droughts and floods, and pushes us toward tipping points — and how we can fight back.

Welcome to Biocentric, a newsletter about sustainability, overshoot, greenwashing, and resistance. It’s written by me, Max Wilbert, the co-author of Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It, co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass, and organizer with the Community Legal Environmental Defense Fund.

If you want to follow, you can subscribe for free. Paid subscribers, in return for supporting this publication and the activism you see here, receive access to private posts which contain behind-the-scenes reports and unreleased drafts.

It's easy to believe, here on the wild edge of a ragged continent, with sand fleas so numerous, they make the sand seem to hop and crawl with life, with seals and river otters and sea otters cruising back and forth in front through the surf, with two buck deer greeting my four year old nephew at the beach and leading him to exclaim, "This is our special moment," with eagles coursing to and fro overhead, with bear and coyote tracks on the sand, that everything is okay with nature.

I want to believe it, deep in the depths of my heart. Every fiber of my being yearns for a world rich with life, vibrant with motion and aliveness and a million, million, million tangled relationship intermingling every day.

But it’s not true.

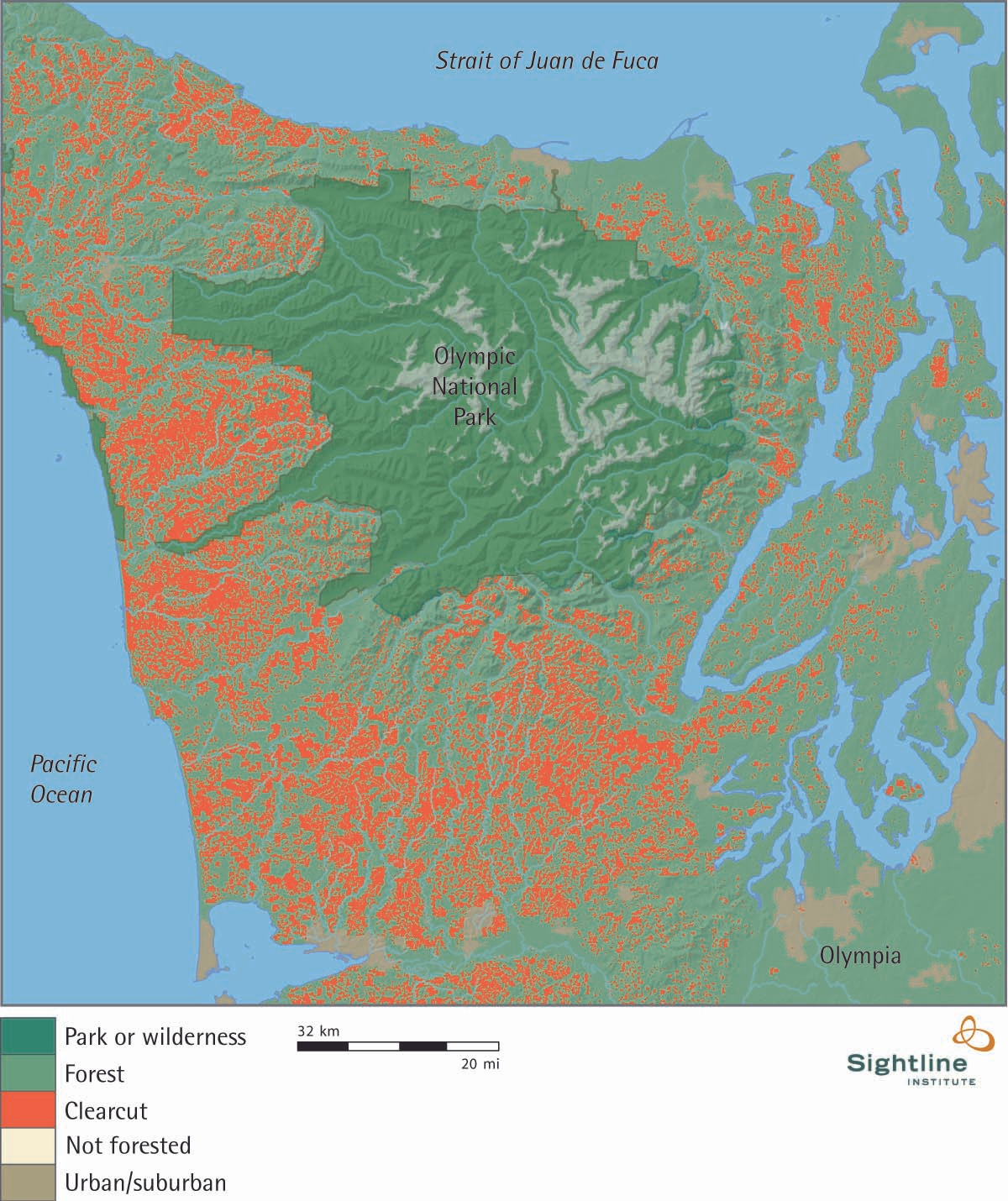

The grizzly bears and the wolves are gone. The old growth is mostly gone. Traveling here, we drive through miles of checkerboard clear cuts where the trees are ripped from the land and the soil is battered and compacted by tank treads. In these places, the precious moisture that the land once held locked under 150 feet of layered shadows is exposed to the harsh wind and sun, evaporating away into the sky. The shading vegetation is gone.

Natural ecosystems generally do with water what permaculturists have long described as “slow it, spread it, sink it.” In other words, they store water in the soil. After logging, much of that soil is compacted and exposed to the elements. Instead of slowing, spreading, and sinking, rainfall tends to pool on the surface, often causing erosion and major landslides before rapidly flowing out of streams and rivers to the sea. When the dry season returns, rather than a dark, moist, shaded forest, there is bare soil exposed to the baking sun. Groundwater drops, and springs and aquifers dry up as base flows decline.

Logging is the dehydration of the land.

It’s the breaking of the “small water cycle,” wherein moisture is slowed and stored in the sponge-like soil and where plants transpire moisture back into the atmosphere — along with microorganisms, salts, and other particles which nucleate rain to fall back on to Earth’s surface. As the headline in Science states, “trees in the Amazon make their own rain.” The same is true, to a greater or lesser extent, for forests and other terrestrial biomes everywhere. The great forests and grasslands of our planet, when undisturbed, lift moisture back into the atmosphere, where planetary wind currents carry it downwind.

of the Climate Water Project has called these “bio-rain corridors.”All of this is both magnified by and accelerates the climate crisis. With warming, extreme weather events — both droughts and heavy rainfall — are increasing. Natural forests provide some level of resilience to these effects by buffering the impacts of flooding, slowing runoff, providing cooling shade, and releasing stored water during times of drought.

In logged areas, just like urban heat islands, the effects of warming are multiplied.

Ecological collapse

What we are seeing here, on the Olympic Peninsula, has happened before. One study of the site of a 6,000-year-old city on Palestinian land now claimed by the Israeli occupying entity found that the urban growth of both modern and ancient cities “involves one of the most extreme forms of ecological stress and land alteration,” noting that “concentration of agricultural, industrial, and commercial activities” in the Akko area led to “a loss of natural biotopes” and a “lack of resilience of coastal ecosystems” characterized by forests that have not grown back despite the city being mostly abandoned for 650 years.

It's what happened in Iraq, in the land of Mesopotamia, between the two rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, in a place that was once called the Fertile Crescent and that bloomed and teemed and exploded with life: hippopotamus, lion, leopard, elephants, and human beings, all mixed together, mingling and chasing and eating each other, living side by side for thousands of years — until people broke the covenant, until they took more water than the land could take, until they started irrigating and plowing and destroying the land and destroying the habitat, all in order to create more food for themselves, for just one species, by taking what the plants produced, by turning habitat into monocrop and harvesting it, year after year, decade after decade, century after century, until the land was exhausted.

It's what happened on the Great Plains when a thousand miles of ancient grasslands fell to the plow and the “Serengeti of North America” was destroyed.

It's what happened along the front range of Colorado, where I've been told that when settler-colonists began killing prairie dogs en masse, the indigenous people told them that the prairie dogs brought the rain, that killing them would be a disaster. This was, of course, dismissed as “primitive superstition.” How could prairie dogs have anything to do with rain?

Only now have scientists just begun to scratch the surface of this knowledge, starting to understand the impacts that those prairie dogs made, billions upon billions upon billions of them digging holes into the soil, creating tunnels by which the fierce storms coming off the Rocky Mountains could trickle deep into the water table, creating the means by which during the dry, long, hot summers, water could rise gently, slowly, quietly, inexorably from those deep aquifers through the prairie dogs tunnels and into the sky once again, into the roots of plants, into the mouths and lungs and cells of animals, humans, plants, other creatures.

I need your help. I’ve left all social media to focus my attention on organizing, coordinating resistance actions, and writing. That means I rely entirely on readers like you to share this content online. If you appreciate what you read here, please take the time to share on social media, discussion forums, and in direct messages to friends. Thank you!

As Madronna Holden writes:

One former prairie dog town stretched 25,000 square miles with its burrows sheltering 400 million animals. When 20th century industry encountered such prodigious lives, it exterminated 98 per cent of them. However, the rains disappeared along with the prairie dogs, as both Navajo and Hopi individuals observed, looking out over the startling barrenness of lands from which prairie dogs were gone. Permaculture creator Bill Mollison proposed this explanation: prairie dog tunnels join those of other earth borers to create “alveoli on the lungs” of the soil that discharge moisture when underground aquifers expand and contract with twice daily earth tides. Thus prairie dog burrows helped conduct water into the air from underground water sources, instigating cycles of rain.

It's what’s happening now in the Amazon Rainforest, one of the new frontiers of landscape dehydration, as vast swathes of forest are cut for palm oil plantations, for cattle ranches, for mines and urban sprawl and charcoal.

When the trees fall, the biological pump that takes water from the soil and puts it back into the sky in the form of evapotranspiration that doubles the amount of rain that would naturally fall without the forest is removed. When that pump collapses, the rainfall collapses.

Tipping points and equilibrium states

This is what is known as a tipping point: a shift in the conditions of the natural community that leads to a new equilibrium situation, a new resting point, a new normal that is hard to get away from because without the original conditions that created the old normal, the new normal has its own inertia. It feels unstoppable.

The conceptual diagram above illustrates this phenomenon using gravity as a reference point. Imagine the ball located at point A as being the normal state of the Amazon rainforest. Without major disturbance, the forest is self-sustaining. If stresses to the forest change a small amount, the “ball” will roll back to point A (in other words, forest will naturally return to its equilibrium point). However, if a large-enough disturbance happens, the forest will breach the tipping point and fall to a new equilibrium at point B, with much lower forest cover.

According to two of the world’s leading experts on the Amazon Rainforest, Thomas E. Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, this is exactly what is happening. “[N]egative synergies between deforestation, climate change, and widespread use of fire indicate a tipping point for the Amazon system to flip to non-forest ecosystems in eastern, southern and central Amazonia at 20-25% deforestation,” they wrote in 2018. “The severity of the droughts of 2005, 2010 and 2015-16 could well represent the first flickers of this ecological tipping point.”

So what’s the current level of deforestation? In 2019, the same authors reported it as: “substantial and frightening: 17% across the entire Amazon basin and approaching 20% in the Brazilian Amazon.”

Another 2024 scientific paper on the Amazon concludes: “the possibility of a near-term forest tipping point by 2030 is real.”

The tipping point comes home

What would it look like for the dehydration of the Pacific Northwest to begin in earnest?

It would look like what we are seeing right now: a phase change, a vast shift in atmospheric conditions, the drying out of the summers, the worsening of the flooding, the increase in wildfires. When I was a child, an 80-degree day in Seattle was something to look forward to a few times a summer. Now, heat in the high nineties and even the triple digits has become commonplace.

All of this is a consequence, not just of global warming, which has been catastrophic, but of the dehydration of the landscape, of the destruction of the old-growth forests, of the spread of urban sprawl and paved areas, and so on.

Forests are reservoirs not just of biodiversity, but of moisture — precious, irreplaceable moisture. They are living sponges that capture every drop of water possible and hold it, gently cradling it in hundreds of miles of mycelium and thick mats of moss, sheltering it in in layers of sphagnum and greenery.

The dehydration of this landscape began long ago. And it's something that we modern humans tend to ignore, because we don't spend most of our time out in the forest: we spend it in the city, the driest places of them all, where the few trees that live are small and isolated in little plots of soil separated from one another by vast expanses of impermeable concrete. Not only are we dehydrating the landscape, but we're dehydrating our understandings of the world.

What can we do?

We can struggle and speak out and put our minds and our bodies and our reputations and our freedom and even our lives on the line for every single scrap of forest, from scraggly urban greenspace to pristine old-growth.

We can build serious networks and organizations dedicated to education, shifting youth culture, and building movement power.

We can contest permits, file lawsuits, write essays, speak at hearings, call neighbors, and pressure politicians.

We can get out on the land — walking, hiking, observing, researching, foraging, following what is happening and where and by whom, so that we rebuild our connection to the places we live.

We can organize protests, tear down survey stakes, setup treesits, blockade roads, and sabotage equipment.

We can even, if necessary, take up arms, when and where that is appropriate.

We can stand up for these forests that make life possible on this blue-green planet.

We can fight back.

“We do not defend nature. We are nature, defending itself”

Thanks for the report and info, Max. The prairie dogs reminded of reading a while ago: uranium in the ground attracts lightning so is a key part of the rain cycle... thus all that uranium mining decades ago most likely affected those cycles. I couldn't find the quote but maybe in "Wisdomkeepers: meeting with Native American spiritual elders" edited by Steve Wall and Harvey Arden. If i do find can let you know.

Glad to see the focus on the Olympic Pen, where I live. I just wrote this piece on the massive decline in the Rufous Hummingbird, which goes right to logging - and the Round-up style chemicals they use to prevent "weeds" like wildflowers. https://substack.com/@schampton/p-161967164